Practice Must Be True Practice

Karin Ryuku Kempe on case 4 in The Gateless Barrier, “Huo-an’s Beardless Barbarian.”

Karin Ryuku Kempe on case 4 in The Gateless Barrier, “Huo-an’s Beardless Barbarian.”

Karin Ryuku Kempe on the practice of listening.

Karin Ryuku Kempe takes up the case of Yantou the Ferryman:

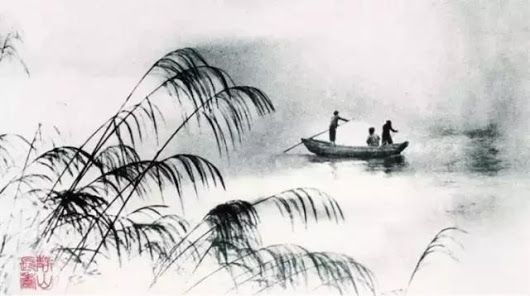

When Yantou was in Shatai, he was a ferryman on a lake in Ezhou. On each side of the lake hung a board; when someone wanted to cross, he or she would knock on the board. Yantou would call out, “Who is it?”or “Which side are you crossing to?” Then he would wave his oars, come out from the reeds, and go to meet the traveler. One day a woman carrying a child in her arms appeared and said, “I have nothing to ask you about plying the oars or handling the pole,” she said, “But where did the child I am holding in my arms come from?” He struck the woman with the oar. The woman said, “I have given birth to seven children; six of them didn’t meet anyone who truly understood them, and this one will not be any good either.” She then threw it into the water. (Zen Echoes: Classic Koans with Verse Commentaries by Three Female Chan Masters by Zishou Miaozong, p. 117.)

Karin Roshi comments:

Can we just let go, immerse ourselves so completely in Mu, in this one breath, this complete moment, that there is nothing that is not completely soaked?

Karin Ryuku Roshi takes up case 20 in the Book of Serenity:

Dizang asked Fayan, “What are you up to these days?”

Fayan said, “I’m wandering at random.”

Dizang said, “What do you expect from wandering?”

Fayan said, “I don’t know.”

Dizang said, “Not knowing is most intimate.”

Karin Roshi comments:

“I don’t know” is actually the absence of any form of identification. It contains both knowing and not knowing, and yet does not stand opposed to either. It takes off our clothes, removes our possessions, even our skin, our hair color and eyes. It’s laying down the karmic burden of our life that we drag around constantly, like a bag of rocks.

In this teisho, Karin Ryuku Kempe Roshi presents an old Zen story of Master Ichu (Ikkyu):

A student said to Master Ichu, “Please write for me something of great wisdom.” Master Ichu picked up his brush and wrote one word: “Attention.” The student said, “Is that all?” The master wrote, “Attention. Attention.” The student became irritable. “That doesn’t seem profound or subtle to me.” In response, Master Ichu wrote simply, “Attention. Attention. Attention.” In frustration, the student demanded, “What does this word ‘attention’ mean?” Master Ichu replied, “Attention means attention.”

Karin Roshi comments:

Really, attention forms the backbone of our practice. As we learn more about the benefits of practicing being mindful, we are learning that there are some important aspects to this paying attention. It has to be intentional, not accidental, and therein lies a kind of effort. It needs to be complete, not split by competing mental activity, daydreams or planning. When our attention is complete, our usual habit of dissociation disappears, and all separation from our life evaporates, falls away. Attention becomes the practice of nonduality. In attention, in awareness, we are our life. Our life is us. There is no gap.